DUNKI: THE PERILOUS PATH TO EUROPE

- 30 Mar - 05 Apr, 2024

"I met a 70-year-old man who had carried his dehydrated wife on his back across the border. He had also been desperate to get medical care for his son who had sustained a gunshot wound. He was forced to leave his other child in no-man’s land while he brought his injured son over for treatment. When he returned for the other child, he was unable to find him. I met him again 10 or so days later and he hadn’t found his other child yet. You could see the desperation and trauma in his eyes. There are stories of displacement and trauma upon trauma, which is tremendously sad,” shares Arunn Jegan, Project Coordinator with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.

History suggests that the Rohingyas have been living in Myanmar since the 12th century. However during the British rule, labourers would migrate to Myanmar from the subcontinent. It was soon after Myanmar gained independence that its government considered the migrants’ move illegal. According to a report issued by the Human Rights Watch in 2000, “The British colonised Burma in a series of three wars beginning in 1824. During their rule, the Arakan problem declined as the British allowed for a relative degree of local autonomy. From 1824 to 1942, there were few recorded incidences of uprisings. This period witnessed significant migration of labourers to Burma from neighbouring South Asia. The British administered Burma as a province of India, thus migration to Burma was considered an internal movement. The Burmese government still considers, however, that the migration which took place during this period was illegal, and it is on this basis that they refuse citizenship to the majority of the Rohingya. The reality is that the Rohingya have had a well- established presence in the country since the 12th century.”

The Rohingyas, are instead labelled as ‘Bengalis’, a shorthand for illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, are based in Myanmar’s western state of Rakhine.

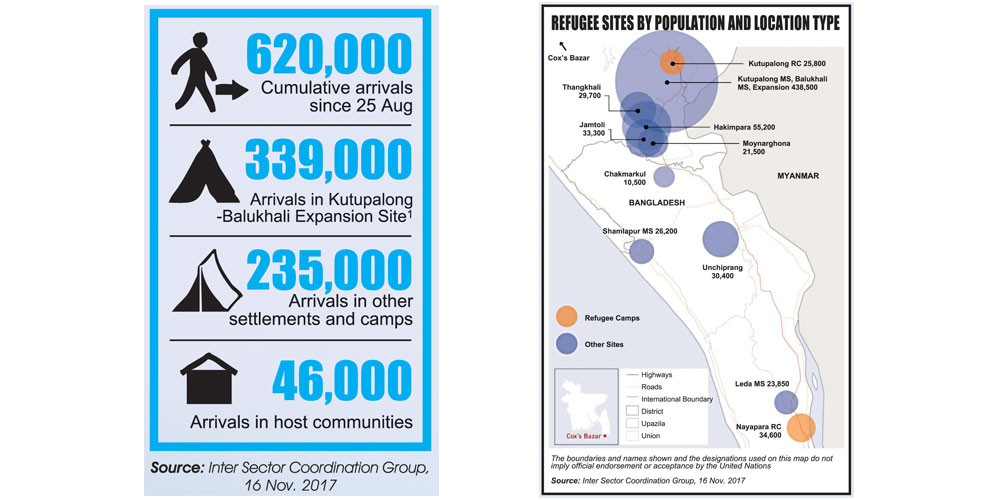

The Rohingyas are considered to be the world’s most persecuted peoples and since August 25, 2017 about 625,000 have fled homes and made long journeys to neighbouring Bangladesh, after a Myanmar army crackdown. The United Nations termed the mass persecution by Myanmar’s military as a 'textbook example of ethnic cleansing’.

In a statement made by the U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, “The situation in northern Rakhine state constitutes ethnic cleansing against the Rohingya… the United States will also pursue accountability through U.S. law, including possible targeted sanctions,” he said referring to the atrocities the Rohingyas have been made to go through.

When MAG contacted the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the UN Migration Agency, in mid-November, for the numbers of refugees who have migrated from the Rakhine, J. Christopher Lowenstein-Lom, spokesperson for Asia & the Pacific said, “I don’t have a number for the diaspora worldwide, which runs into millions, notably to Malaysia and the Gulf states; some 836,000 are currently in Cox’s Bazar (CXB) district of Bangladesh.”

With vast numbers of Rohingyas fleeing their homes in Rakhine since August of this year, Lowenstein-Lom marks out the hindrances the IOM team faces on ground. “(There is) very limited infrastructure, including road access, water, sanitation and healthcare.” As for how many have been moved to safer locations, he shares, “None recently, as the Bangladesh government wants to keep the Rohingya population in CXB district, where they can access aid. Small numbers of Rohingyas have been resettled from Bangladesh to third countries in the past.” But is it easy for them to leave their homes behind? “Their homes are in Myanmar, they do not want to leave, but have been forced to due to ethnic cleansing by the Myanmar military and local Buddhists,” Lowenstein-Lom adds, making it known that “IOM does not have access to North Rakhine State, where their homes are located.”

“For some, the journey has been four days and for others it has taken up to 12 days to cross over,” Jegan shares the time it takes for the Rohingyas to reach safer areas of Bangladesh. “Some have walked for up to two weeks across Rakhine state in Myanmar before reaching Bangladesh. They walk or travel by boat to Bangladesh, then they walk or get a ride in a truck to the CXB settlements,” Lowenstein-Lom adds.

‘Majority (of the migrants) arrive at the southern tip of Shah Porir Dwip, an island where the Naf River meets the Bay of Bengal’, according to Time magazine, with “People arriving in a very vulnerable state after walking for days to get here. Upon arrival, they have a very short time to build basic shelter using bamboo poles and plastic sheeting,” Jegan marks out the conditions of the camps which are getting congested with each passing day and finding a place to settle the refugees is becoming increasingly difficult.

When speaking to Katherine Lynn Bundra Roux, Communications Coordinator of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Regional Delegation Bangkok, majority of the refugees are moving to Bangladesh. “But there are also large numbers of people that have been displaced within Rakhine State,” to whom the ICRC is providing aid. “We are providing aid on a daily basis to people who have been forced to leave their homes and they have nothing left. Those left in Rakhine are extremely vulnerable, and they need help." On Bangladesh’s side, Roux has been informed by her colleagues that “The situation is still fluid and people are on the move; some have settled and others are still looking for shelter. Some days the influx goes down or stops and other days it resumes. It all depends on the situation on the other side. Most of them arrive exhausted and traumatised, and have few belongings with them.”

However, Roux’s team members on ground do face difficulties while serving the destitute. “There are various challenges including the fact we have been forced to reduce our movement in certain areas due to security reasons, the remote locations of people in need, poor road and other infrastructure, monsoon rains and a looming cyclone season,” she talks about the tight situation the members come across during their operations.

In Dhaka, Misada Saif, ICRC’s Prevention/ Communication Coordinator over email shares the activities her team is carrying out, which includes “Restoring Family Links, a mobile health clinic and food assistance to help people with their basic necessities.” Her team members have assisted about “15,622 patients who have received mobile health services” till the time this piece went to print.

Saif commends the host communities on their hospitality, “Bangladesh has been dealing with this crisis for the past 30 years. The host communities have showed tremendous and amazing hospitality to the new comers. However, this influx caused severe stretch on the infrastructure and public services which complicated things for both the new comers and Bangladeshis.”

But do the Rohingyas feel safe in Bangladesh, or do they plan on heading home once the conflict is over? According to Saif, “For families to consider returning home, trust must be rebuilt at all levels between communities in Rakhine, so that they may peacefully co-exist.”

Jegan, who has been serving in the overwhelming situation points out, "From what I have heard, the Rohingya feel safe in Bangladesh, but the difficulty is the lack of identity or recognition both here, and in Myanmar. People tell me they will not return, unless they are legally recognised. The challenges are not over for the Rohingya population who have crossed the border – the situation in the camps is precarious and requires ongoing, consistent relief from all the international actors, including MSF.”

Suffering by the people in the Rakhine goes back decades and a statement issued by Director of Global Operations for ICRC, Dominik Stillhart states, “People in Rakhine State have suffered from decades of underdevelopment, poverty, and intercommunal violence. If cyclical violence is to be halted, communities' grievances must be addressed... following the violence and fear of violence that has driven residents to flee their homes, all communities are now suffering from severe shock. It feels dangerous to move, so people stay in place, meaning limited access to schools, farm fields, markets and healthcare.”

A ray of hope did kindle on November 25, 2017 when Reuters reported that 'Bangladesh and Myanmar have agreed to take help from the U.N. refugee agency to safely repatriate hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslims who had fled violence in Myanmar." With more than 600,000 having sought refuge in neighbouring Bangladesh, the Bangladesh Foreign Minister Abul Hassan Mahmood Ali said, “Both countries agreed to take help from the UNHCR in the Rohingya repatriation process. Myanmar will take its assistance as per their requirement.”

This came about before Pope Francis was to visit Myanmar and Bangladesh from November 26 to December 2, 2017 who did not use the 'R' word while in Myanmar. On his flight back from Bangladesh, he explained to journalists why he did not use the word Rohingya. "Had I said that word, I would have been slamming the door. What I thought about it was already well known," he said.

Jegan mentions the makeshift settlements where MSF has medical facilities in Cox’s Bazar include Kutupalong, Balukhali, Thangkali, Hakimpara, Jamtoli, Moynarghona, Putibunia and Unchiprang, while Saif states, “We operate from the city of Cox's Bazar and maintain a presence there for our projects such as food distribution, restoring family links and mobile health clinics. This means we operate in the major camps such as Kutupalong and Balukhali but we also focus our daily operations on the border areas of Bangladesh and Myanmar, such as Kornapara and Borochankola.”

The teams of humanitarian organisations which have been serving the destitute, face logistical and operational challenges due to hilly areas and extreme weather. “It’s difficult to accept that we’re seeing a refugee crisis of this scale in 2017. It is difficult for our medical staff to see people suffering from preventable diseases, and having to treat patients with limited resources on the ground,” Jegan highlights.

COMMENTS