THREADS OF SUCCESS

- 06 Apr - 12 Apr, 2024

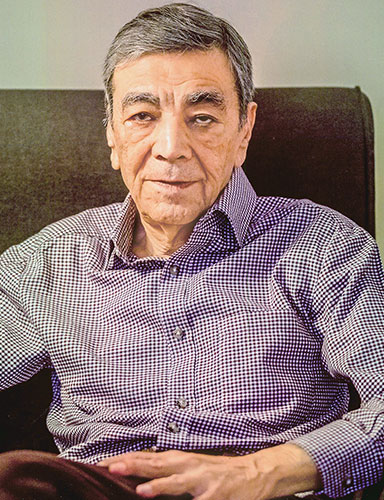

Eight hours prior to his performance at the Madinat Theatre, Zia Mohyeddin is a picture of composure. We meet the octogenarian in Karama; music and hearty laughter are in the air. As Mohyeddin settles down on a sofa right next to a brightly-lit lamp, the lines on his face, accentuated by the glare, seem to tell a story, much like Mohyeddin himself. Stories of perseverance, endurance and deep-rooted passion that has transformed the cultural landscape of Pakistan.

It says something about an artiste’s legacy when it is so robust that he or she cannot be boxed in a singular category. Mohyeddin has been an actor and a director, he founded Reader’s Theatre in Pakistan and has helmed one of the most popular talk shows in the country, apart from founding the National Academy of Performing Arts (NAPA). He is also a master orator. Even those who do not follow the Urdu language have been left entranced by his eloquence. That’s the power of his deep, baritone voice. That’s the power of being Zia Mohyeddin.

His journey to the West has been well documented. Having studied acting at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts in London, Mohyeddin went on to star in some iconic English and Urdu plays. What followed were a spate of English language films like Lawrence of Arabia, Sammy Going South and Khartoum, among others. As passionate as he is about these films, the 84-year-old veteran artiste is most enthusiastic when he talks about a performance on stage. “To me, it does not matter what the ‘atmosphere’ is like. If I were to go to Tanganyika, it’s my duty as a professional actor to convey whatever best I know regardless of whether it is understood, absorbed or appreciated. I member I was performing in Delhi once and almost 70 to 80 per cent of the audiences, who weren’t Urdu-speaking, were interested in the language. That gave me tremendous heart because there was curiosity.”

Audience’s curiosity is a great compliment for an artiste and Mohyeddin evokes it ever so often. Look at the iconic scene from Lawrence of Arabia where Mohyeddin’s character is shot dead for drinking water by Omar Sharif’s Ali. Today, the film is regarded as an all-time classic. “Or so they say,” quips Mohyeddin. “It’s largely because of David Lean, the director, who was a perfectionist to the core but also enjoyed his sadism. Sometimes, he’d go on with this sadistic streak and put an actor to misery. Having said that, I must admit that among all the directors I have worked with, the eye for detail that he had, no one else did.”

The ‘eye for detail’ wasn’t simply about substituting a red background with a white, says Mohyeddin, and soon begins to tap his fingers on the table. The first time, he taps rather quickly, while later, he does so only twice. “If David Lean was around, he’d say, ‘You can do it once, but do you think this character demands constant tapping?’ This iota of change would be reflected in the way he’d move his camera. The totality of the scene would come across to the audience.”

An actor, he says, wants to please his director. Was James Ivory, in whose Bombay Talkie he acted in, one of them? Even though he remembers his co-stars, the late Shashi Kapoor (“he was extremely kind to me”), Aparna Sen (“she was a newcomer then, but extremely gifted”) and the late Utpal Dutt (“we would have discussions on the Bengali language”) rather fondly, it was Ivory’s approach to film-making that left Mohyeddin intrigued and inspired. “He wouldn’t elaborate on what he wanted. He’d say, ‘Try it again.’ You knew he was satisfied only when he would proceed to the next shot. He wouldn’t say, ‘Well done,’ which was exactly what I wanted because it made me want to do more. Cinema is actually a director’s medium.”

Theatre, on the other hand, is a different ball game altogether. Mohyeddin contends that it is not people’s entertainment and hence, its evolution in any part of the world cannot be easily judged. “In our part of the world, we have a limitation. We are not meant to portray certain religious figures on stage. However, through our efforts at NAPA, people have come to accept that we can tackle all kinds of subjects. Nothing should be considered a taboo. Of course, we cannot have nudes. So, an Oh Calcutta is out,” jokes Mohyeddin, adding. “In India, you have a 2,000-year-old tradition of dance dramas. But dance is not usually looked upon as something shareef log (honourable people) would do. But who are these shareef log? Ninety per cent of them are hypocrites who’d otherwise enjoy the most vulgar dances.”

Lately, there’s been talk of Pakistani films getting a new lease of life, the road to which has been carved by the dramas. Interestingly, many of the dramas are inspired by Urdu novels. Mohyeddin acknowledges that “some experimentation has been done, but mostly by amateurs”. “If done professionally, dramas would have greater depth. Our cinema, however, hasn’t matured at all,” he says.

In the 70s, Mohyeddin became a household name with his talk show The Zia Mohyeddin Show. Today, he looks back at those days with fondness. “The adulation I received was immense. I had total editorial control and would decide who’d be invited.” Things turned awry when “authorities” began to intervene. “Some higher ups hinted I should seek permission before inviting someone. I told them I wasn’t planning to topple the government. I sensed there would be censorship and decided to leave the show. In hindsight, it was sensible.” Today, having founded NAPA and nurturing it through the years, Mohyeddin has become one of the most important figures in Pakistan’s arts and culture scene. An aesthete whose legacy is as humongous as his talent.

Source: WKND Magazine

COMMENTS