MUSLIMS ENTER AMERICAN POLITICS

- 10 Nov - 16 Nov, 2018

My mother, born in 1938, had a highly fruitful career of more than four decades devoted to American public education. She used to invite me to visit the school where she was principal, to speak to classes about writing. I remember one time sitting on a little chair in a classroom, in conversation with a six-year-old, and making a passing reference to her. “You know my mom,” I clarified. “Mrs. Casey.” The boy’s eyes grew wide: “Mrs. Casey is your mom?!? You’re lucky!”

My mom, Mrs. Casey, is all about education. Another thing about her is that she hates bullies. Being alert to bullies and bullying is part of the job of an elementary school principal, after all. So you can imagine what my mom thinks about Donald Trump.

Mind you, Trump is not the only bully in public life who gets on my mom’s nerves. Others she also can’t stand include not only “Bully Bush” (as she called him throughout his long eight years in office), the perpetrator of the cynical “No Child Left Behind” policy, but also the highly lauded education reform advocate Bill Gates and his co-conspirator Arne Duncan, Secretary of Education under Obama. And that’s the thing: The Trump regime may be the beneficiary of what some are already calling the destruction of the American public education system, but that destruction was initiated under Bush and continued under Obama. The mess American society now finds itself in is not all about Trump. Trump is only the end result.

Education as a public institution has been a battleground in America for decades now, and Trump’s appointment of Betsy DeVos as Secretary of Education was a kind of culmination, a very explicit statement by the robber barons of our time, just like Scott Pruitt as head of the Environmental Protection Agency. The idea in both cases is to “destroy the village in order to save it,” as an American officer is reputed to have said, without intended irony, during the Vietnam War. The point was – and is – not to save the village at all, but simply to destroy it.

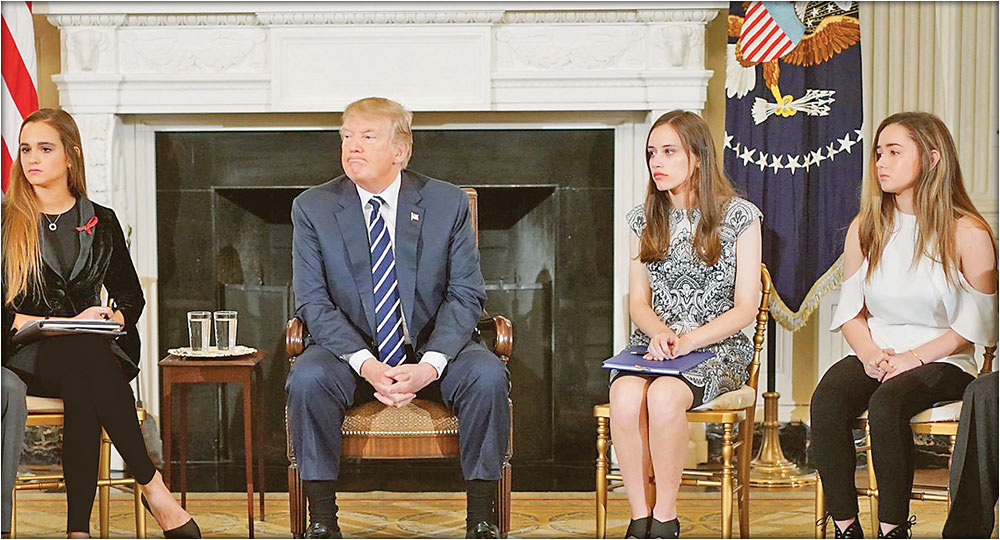

The aftermath of the Feb. 14 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida has American society, such as it is, enduring another spasm of bitter and fruitless recrimination posing as policy debate. The unexpected moral and rhetorical leadership of the surviving students themselves – notably Emma Gonzalez and David Hogg – suggests that there just might be something new under the sun after all. But whether the hulking behemoth that is the American body politic can be righted is very much an open question. Seventeen-year-old David Hogg might have been asking for more than can be expected in the circumstances when he told CNN: “We’re children. You guys are the adults. You need to take some action and play a role. Work together.”

All of a sudden, for now – until the next crisis – “school safety” is the buzz phrase of the moment. Trump speaks of a need to ‘harden our schools,’ and the White House is claiming to have the funds to arm one million teachers. (That number of hypothetically armed teachers, one million, is roughly 1/300th of all the human beings in the United States of America.) The regime’s designated hard man, Vice President Mike Pence, ‘pledges’ that ‘school safety’ will be a ‘top national priority.’ I make no apology for my use of scare quotes, because there is no grounds for believing in the sincerity of intention in such phrases, coming from such people. Mike Pence isn’t entitled to tell me what America’s national priorities should be. It’s not possible to have what we fondly call “a national conversation” when the people elected to lead one are so utterly lacking in moral authority.

Meanwhile, all of the public school teachers in the state of West Virginia have staged a walkout, protesting against low pay and poor benefits and leaving 275,000 students at home. The strike echoes the now largely forgotten (yet historically significant) standoff between public employees – led by teachers – and the radical right-wing state governor Scott Walker in my home state of Wisconsin in 2011-12.

All of the above prompts musings about education as a public good, as well as about the nature of education itself – what education is. If the education of a society’s children – not ‘school safety,’ mind you, but education itself – is not an agreed-upon national priority, then what is the nature of the nation itself? Boy, is that ever a big and urgent question. And, to get back to basics, what is education anyway? My father once told me what he was proudest of about me was that, as an adult, I continued to learn and study on my own initiative. In middle age, I continue to take that to heart.

The novelist Marilynne Robinson recently spoke of how Americans in public life are “expected to have mastery of an artificial language, a language made up arbitrarily of the terms and references of a nonexistent world that is conjured out of prejudice and nostalgia and mis- and disinformation, as well as of fashion and slovenliness among the opinion makers.” If, as she claims, such a ‘dialect’ is “pervasive in ordinary educated life,” then is not the purpose of “ordinary” education to propagate “prejudice and nostalgia and mis- and disinformation”? In the same essay Robinson recommends, as an antidote, “wander[ing] now and then into the vast arcana of what we have been and done” – i.e., thinking and reading for oneself.

Often these days, I find myself engaging in the thought experiment of wondering what I would do if I were raising school-age children in today’s America. Children need social development – to be among other children – as well as knowledge, so schools do serve a purpose. But I sometimes wonder if the best thing for my hypothetical children, for their spiritual and intellectual well-being as well as their physical safety, might hypothetically

be to keep them at home, reading books. •

COMMENTS