Agora Open Air Museum

- 18 Nov - 24 Nov, 2017

Eleven hundred years ago Muslims were manufacturing paper in Baghdad after the capture of Chinese prisoners in the battle of Tallas in 751. The secrets of Chinese papermaking were passed to their captors, and papermaking was quickly refined and transformed into mass production in the mills of Baghdad and spread westward to Damascus, Tiberias, and Syrian Tripoli. As production increased, paper became cheaper and of better quality, and it was the mills of Damascus that were the major sources of supply to Europe.

The Syrian factories benefited greatly from being able to grow hemp, a raw material whose fibre length and strength meant it produced high-quality paper. Today, hemp paper is considered renewable, environmental friendly and also costs less than half as much to process as wood-based paper.

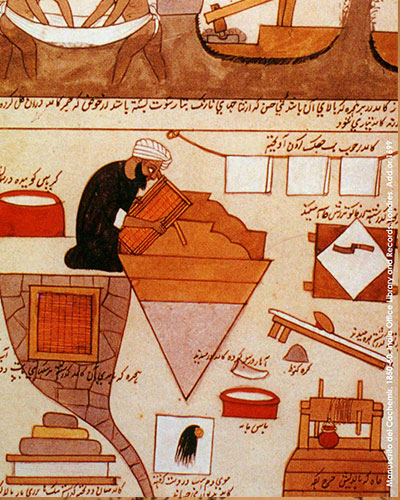

As well as hemp, Muslims also introduced linen as a substitute for the bark of the mulberry, a raw material used by the Chinese. The linen rags were broken up, soaked in water, and fermented. They were then boiled and cleared of alkaline residue and dirt. The clean rags were beaten to a pulp by a trip hammer, a method pioneered by Muslims.

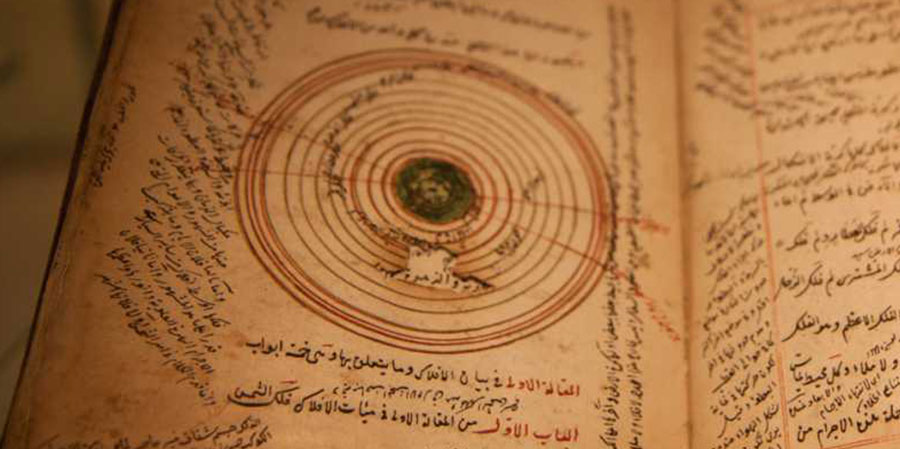

They also experimented with raw materials, making cotton paper. A Muslim manuscript on this dating from the 11th century was discovered in the library of the Escorial in Madrid.

By 800, paper production had reached Egypt, and possibly the earliest copy of the Quran on paper was recorded here in the 10th century. From Egypt, it travelled farther west, across North Africa to Morocco. Like much else, from there it crossed the straits into Muslim Spain around 950, where the Andalusians soon took it up, and the town of Jativa, near Valencia, became famous for its manufacture of thick, glossy paper, called Shatibi. Within 200 years of it being produced in Baghdad’s mills, paper was in general use throughout the Islamic world.

This meant that producing books became easier and more cost effective because paper replaced the expensive and rare materials of papyrus and parchment, so mass book production was triggered. In the Muslim world, hundreds, even thousands, of copies of reference materials were made available, stimulating a flourishing book trade and learning. However, the revolution in bookmaking was to happen much later after the use of printing machines in Europe.

Danish historian Johannes Pedersen said that by manufacturing paper on a large scale, the Muslims “accomplished a feat of crucial significance not only to the history of Islamic books but also to the whole world of books.”

COMMENTS