THREADS OF SUCCESS

- 06 Apr - 12 Apr, 2024

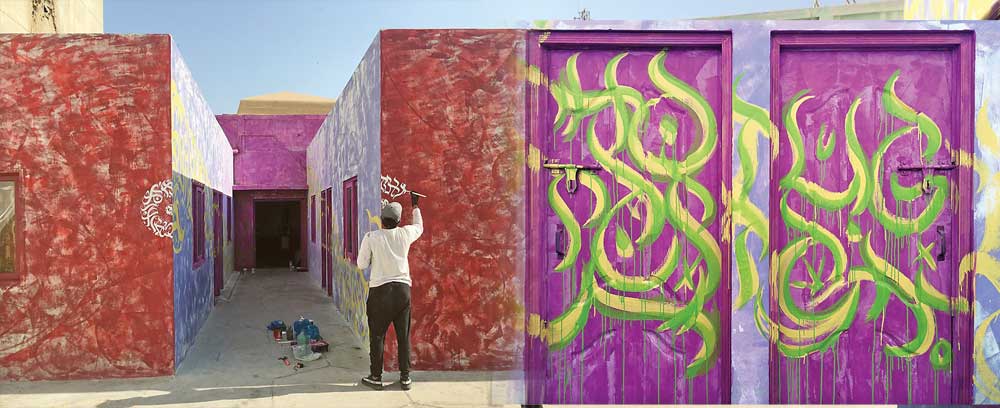

He is the most famous – if not the only graffiti artist of Pakistan – named Abdullah Ahmed Khan aka Sanki King. With his contribution to the Karachi Biennale 2017 – Mind Palace - Freedom of Thought – the 27-year-old has now officially arrived in the art world – a world that doesn't really know what to do with this over-confident former rapper, beatboxer and DJ who uses his remarkable technical skills to fuse graffiti with ornament, eastern tradition with western street culture. His confidence can be quite intimidating sometimes, and it’s probably why some people don't like him. On the other hand, it can also be inspiring, for it is fun to listen to this self-assured graffiti king, and without this confidence, he may not be able to paint like he does – creating those beautifully clear and balanced artworks on the spot, in a freestyle manner. You can see his confidence in his brush strokes that show no sign of hesitation and only need little after-treatment, if any. He has every reason to be proud of his achievements: developing a unique style that is immediately recognisable, which is not an easy thing to do, for some artists never get there. He is definitely on his way, reading people like Carl Jung, Alan Watts and Ashfaq Ahmed. I met Sanki at the Jamshed Memorial School and had a candid chat with him while he worked on his large-scale artwork.

You have always faced resistance from other established artists and it seems they don't consider your work as 'real art’. Why is that so?

Sanki King: Firstly, if you don’t have an art degree, then you are not accepted. A lot of people have told to me that I am not an artist because I don't have a degree. Previously, some have even gone as far as saying that if you don’t have an art degree, you are no better than an electrician or a car mechanic.

Tell us a bit about your participation in the Karachi Biennale, about your work and the location you are to exhibit it?

SK: All the artists who are working for the Biennale were actually assigned places to work at. All the 12 locations of the Biennale were divided. The location I work at is actually one of the biggest, while the biggest one is NJV School. I was told to paint on a rooftop and had no idea how big it was. So when I came here initially, my plan was to paint the walls of the passageway and a few walls outside. But because I had a very good budget, I decided to go all the way and paint the floor, while also creating a big piece right at the centre of the courtyard. Therefore, this space is a part of my mind and I think of it as my 'mind palace'.

It's obviously not essential to understand the piece; it's the message that lies there. Do you like the idea that it is encoded, but also hidden at the same time?

SK: Yes, that is exactly what it is. When people understand something, it becomes boring for them. But if it’s a mystery, it keeps them interested. For instance, in relationships, people run after those who are hard to get. But it is also because I’m really fascinated by Arabic text.

Are you the only artist who paints English calligraphy or graffiti which looks like Arabic?

SK: I'm not sure if I'm the only one. A lot of people have told me that I’m a scam, because they can’t make anything out of my work. So I had to take them to my pieces and make them read, and that’s when they understood the depth of my work.

Do you think that a piece of artwork is still art, if one fully understands it?

SK: Yes, absolutely. But there's another aspect: you can understand an artist’s perspective and where they are coming from, but obviously you cannot feel how they feel. For instance, if I put up this big poster which has an artist’s statement on it and clearly speaks about his work, there would still be people who wouldn’t understand it in the artist’s way but they’ll have their own perception of it. So it is all subjective. My work is a mixture of different things. I cannot look at any of my works and say that it is related to a particular theme, for a lot of times I'd do a piece inspired by a song and people would perceive it to be inspired by some religious Arabic text.

Is there an example of a specific song that inspired you to do a piece?

SK: Yes, but it’s a graffiti piece. It is a song by one of my favourite DJs, Darius. He does French house, and it’s called Espoir. I also love Hostias from Mozart's Requiem, which is one of my most favourite pieces.

Do you only work with walls, and would you consider it a kind of betrayal of graffiti art if you started painting on a canvas?

SK: No, but I really love scale. I work in phases, so there would be a phase where I would only paint screens or canvases, while other times I would only paint walls. My canvases are 3x4 feet, 6x8 feet small canvas for me is very confining, since and I'm used to paint 40-60 feet walls. Similarly, these walls and passageways are literally like a piece of paper for me, which is why you’d never see me creating an initial sketch of an artwork on a wall first and then going over it later. I just need to stand in front of a wall and see the final work on it. I’ve gotten so used to painting and then visualising the final pieces that I don’t need to do any initial sketches.

Apart from Sadequain, you're probably the only Pakistani artist producing large-scale calligraphy pieces, but do you consider yourself a Pakistani artist at all?

SK: No, I don’t believe in boundaries and names. I look at myself as an artist and that’s it. Take me to the USA, Germany, Czech Republic or anywhere else, I’d be the same. All the people around the world are one. For me, home is not just Karachi, it is the entire world. I don’t believe in these social constructs; even though I wanted to become famous in Pakistan first – in my city, Karachi where I grew up – however, I’m open to work anywhere around the world.

Why is there no graffiti art scene here?

SK: Any kind of art other than the one what you can already fined in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and all these other places is not being accepted. We have the worst copies of those original artworks in Pakistan – made by all these graduates – most of the art in the Pakistani art community, around 80-90 per cent is all copied and stolen concepts.

When it comes to artwork, I guess Karachi is called the 'Capital of Piracy'. What do you think?

SK: It is because of a popular belief, that the aspiring artist or beginner needs an art degree if they want to make a career in the field. So, many of them go to an art school and are taught specific work according to the school’s agenda, and teachers want them to draw and paint as they themselves like, not how the students want to paint or draw. When they are out of these schools, many of them are literally begging for collaborations, residencies and art exhibitions. Those who can get them are exploited by the art exhibitions that ask them to get an art residency, if they want their art to be more valuable and the vicious cycle of exploitation continues. Art school teaches them to produce work that is considered admirable by the museums, collectors, elite, corporate groups such as big banks who collect artwork. They are forced to lead a career like that because it has good money. So, it’s a pretty miserable state to be in. This is why people were against me and have not supported me in the past, because I have broken a lot of barriers in Pakistan’s art scene. I have been internationally known since I was 21, while art students get a degree at the age of 24. This has sparked anxiety among the art world and other artists.

But you are very confident and not afraid of anyone. Why is that?

SK: It probably has to do with the way I was brought up. I had a very learned father. My grandfather used to work in the Supreme Court, my uncles were criminal lawyers, and my father worked for the interior ministry of Saudi Arabia, so he knew influential people. Back in 2012, I was already doing art and was confident, but suppressed in some way. Then I started meditation, and at the same time, I also began doing big projects, which also gave me a lot of confidence. This is when my alpha side came out, when I was around 24, and some very powerful friends.

Why did you choose ‘Sanki King’ as your moniker?

SK: In the graffiti world, when you reach a very high level of respect, they have certain titles for you. A female graffiti artist is called the queen and a male graffiti artist is called the king. If an amateur or average graffiti artist call themselves king or queen, they are disowned by the graffiti community throughout the world because everyone knows each other. Wherever you go in the world, most of the graffiti artists would know me by name. I was actually given the name ‘King’ by my some very old, well-known and old-school graffiti artists from the graffiti community in New York and then I was taken into these world-famous graffiti crews.

Why ‘Sanki’ and how did you get the name?

SK: ‘Sanki’ is an alternative word for pagal in Urdu to call someone crazy. But the real meaning of ‘Sanki’ is deep thinker. I believe it’s a Hindi word, for I have seen it in old Indian movies. I got the name while I played an online game called Counter-Strike and was really good at it, and people would say, ‘Your game is so good, you are sanki!’ Then a year later, I started parkour and b-boying, and my friends who saw me doing it, started calling me‚ sanki.

Have you ever been a vandal when you started graffiti?

SK: Never! The very reason I started graffiti back in 2004-2005 was because I wanted to show people that the only use of spray paints is not writing political and religious slogans on the streets and public/private properties. In fact, they can be used to create art as well. I had been introduced to hip-hop since 2001 so I already knew plenty about aerosol art, and looking at all the vandalism around Karachi made me want to throw up. Graffiti and fine art was just a hobby for me and back then, I never imagined I would be such a skilled and well-known artist one day.

Did your family support you or put up barriers in your work?

SK: The only two barriers that I had were bad experiences with some old friends and a few people in the media and art world, who were exploiting me. They gave me projects, saying that it would give exposure but did not pay me for then. While barriers in my personal life were mostly emotional: my mother passed away when I was eight and my father passed away when I was 21, so my feelings got bottled up but came out after my father’s death. Therefore, the barriers were inside me with a lot of emotional debris. My sisters would often ask me if I really wanted to do this for a living because it is so hard living in Pakistan as an artist. It was much harder for me, because I was doing something that nobody else was doing.

COMMENTS