MUSLIMS ENTER AMERICAN POLITICS

- 10 Nov - 16 Nov, 2018

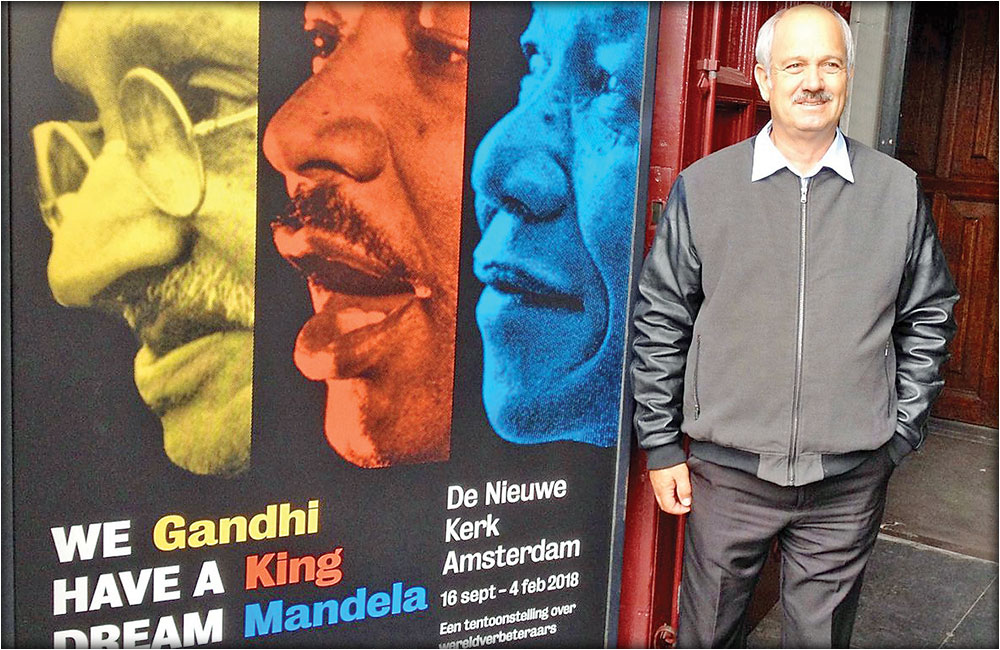

Christo Brand is an Afrikaans-speaking white South African, a country boy who grew up on a farm during his country’s notorious period of apartheid, or legally enforced racial separation.

When Brand was growing up, military service was obligatory in South Africa for all young white men, and many were required to fight rebels in neighbouring Angola or to police the restive segregated “townships” where black South Africans were forced to live. After a friend joined the army and was killed, as Brand saw it, for no good reason, he began looking for alternatives. One permissible option was to join the prison service. So Brand signed up to become a prison guard – and it changed his life, to put it mildly.

At the infamous Robben Island prison off the coast near Cape Town, Brand at age 19 was told that the prisoners in his charge were among the most dangerous criminals and terrorists in the country. Over the years to come, he came to know them by name and as friends. Those men are now celebrated worldwide as exemplars of political heroism: men such as Ahmed Kathrada (fetchingly known to his friends and admirers as “Kathy”), Walter Sisulu, and Nelson Mandela.

All of the above and more is recounted in Brand’s remarkable book Mandela: My Prisoner, My Friend. The overriding message of the book, and of Brand’s public speaking and indeed his whole life, is an urgently needed one, now as much as during the dark years of apartheid South Africa: mutual respect among human beings across the lines of race, religion, and political faction that ostensibly divide us.

I first met Christo Brand in June 2016, in his home city of Cape Town, when he spoke to a group of students I was traveling with from Texas Christian University. The students were visiting South Africa to study the crisis in poaching of endangered rhinoceros for their horn. Our dinner with Brand was a bonus that I had been able to help arrange, because my mother and brother had bumped into him years earlier on the ferry to Robben Island and struck up a conversation and then a friendship. On February 28 of this year I was in Fort Worth, Texas, to hear Christo speak to students and for other work that I do with TCU. My parents and brother flew in from other parts of the United States just to see Christo, and we got to share several meals with him and his wife.

Part of what is remarkable about Christo Brand is that he is not an “expert” in anything, or powerful, or highly educated. He is only a deeply decent person who knows right from wrong and has a correct understanding of history and our place in it as individuals and communities. The thing he said during our days together at TCU that was most memorable to me was, “There were rich whites and poor whites. They [the apartheid regime] just used the poor whites for their vote.” The Brand family were poor whites; Christo’s father was a farm manager – essentially a sharecropper, perpetually struggling to make ends meet – and Christo was the only white child on the farm.

During and after his speech to TCU students, I found myself wondering, first of all, whether “young people these days” really know or appreciate just who Nelson Mandela was and what he accomplished. If not, they have that still to learn, and of course, there are equivalent struggles – and, we can hope, Mandelas – in our own time. In any case, bringing the author of Mandela: My Prisoner, My Friend all the way from South Africa was a tangible and meaningful expression of TCU’s own self-declared mission “to educate individuals to think and act as ethical leaders and responsible citizens in the global community.”

In his introductory remarks TCU’s provost, Dr Nowell Donovan, exhorted the university’s mostly privileged American students that other countries “have different stories to tell. It’s different, and it’s enriching. Just do it. Say, ‘I’m not just going to stay in Texas. I’m going to get out and see the rest of the world.”

TCU student Jodi Trevino was in the group I accompanied to South Africa in June 2016, and Christo Brand made a big impression on her.

“I got to sit next to him, which was really cool,” she told me. “Some of the things that he said really stuck out to me. One of my questions to him was about the United States and what he thinks, not only about the [2016 American presidential] election, but about acts of police brutality and racism. And he said that this election is crucial in the context of the things that are happening in the United States. Depending on who we elect, it will have a big impact on the things that are happening in our country. He said it was fearful to witness, because he grew up during apartheid, and the way he saw elections happen looked very similar to what’s happening now [in the U.S.].

“Direct quote: ‘I could never hate a white man, only the system that made him that way.’ Which is extremely profound, because when a lot of things happen, at least in the culture that I live in, the immediate response is to hate the person who did them. These natural microaggressions are weaved into our history as a nation. When he said that, I realised that, ‘Wow, we really have a lot of work to do.’ My dad tells me that now people are treating him the way they were treating him in high school. The way that your government is, and the way that they treat people, is indicative of how people will treat others. White South Africans who were genuinely nice and kind and wanted to be nice to black people, couldn’t be. They were able

to strip away your humanity and your kindness. And you don’t realise that, if you’re not paying attention.”

COMMENTS