Social Media to you is?

- 27 May - 02 Jun, 2023

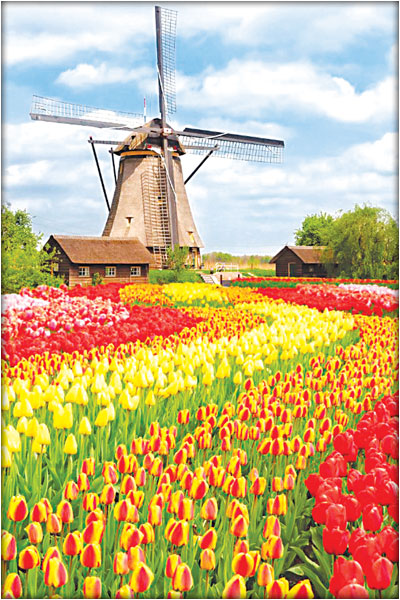

Think of the Netherlands and the enduring images that come to mind are windmills, wooden clogs and… tulips. But tulips are not indigenous to the tiny nation. They come from – depending on whom you talk to – somewhere in Central Asia, Kazakhstan or Afghanistan.

Tulip bulbs were given to visiting dignitaries by the sultan of the Ottoman Empire, with the plants first cultivated in the Netherlands in 1593. The name ‘tulip’ derives from ‘tulibend’, the name of the turban worn in the area (now modern Turkey) because of the supposed resemblance of the flower to a turban.

Tulips have long been a force in the Dutch economy, and were even the source of the world’s first ‘investment bubble’. Back in the early-17th century, the tulip’s value escalated so precipitously that one bulb could cost as much as a house. Then, in 1637, thousands of people lost everything when a plant virus brought the whole value system crashing down. Cartoons depicting this folly can be found in Dutch galleries as, in the years following, artists added tulips to their paintings as an aside commentary meaning ‘foolish.’

Today the tulip continues as a mainstay of the country’s economic life, and it plays an important role as the cornerstone on which the Netherland’s leadership as the largest purveyor of plants and sees in the world is built. It all takes place at Royal FloraHolland, the world’s largest flower auction company, where today more than half of the world’s flowers move from grower to distributor and then on to the retail customer. It is indeed the Netherland’s ‘Wall Street for Flowers’.

Royal FloraHolland is a showcase for Dutch expertise in logistics. More than 12 billion plants and flowers – including more than 90 per cent of the Netherland’s own output – change hands each year at Royal FloraHolland’s four marketplaces throughout the country. The contribution to the Netherland’s economy is profound: more than 250,000 jobs are the product directly and indirectly of the flower markets.

Royal FloraHolland is a cooperative with 4,500 members, 9,000 suppliers, 25,000 customers and 3,000 employees. The largest of the markets is at Aalsmeer, just below Schipol Airport, south of the centre of Amsterdam. Here, in a huge concrete building, hundreds of mini-trucks hauling wagons full of plants and flowers whizz around other workers on smaller vehicles in an area the size of 200 soccer fields – approximately 990,000 square metres.

The flowers arrive daily, usually overnight, for the auction five days a week, which starts at 6 a.m. and ends around 10 a.m. Elsewhere in the building, Royal FloraHolland customers – flower sellers ranging from small family-owned outlets to mega chains, such as Tesco in the UK, are bidding against the clock on the millions of flowers sold each day.

The auction works in reverse: rather than bidding up the price, Royal FloraHolland’s auction bids down.

The bidding system is based on backwards: buyers stop the clock at the price they want to pay and then advice how many plants they want.

Then the clock resets. The process moves at lightning speed. In the time it takes you to read this paragraph, Royal FloraHolland would have sold perhaps ten lots of flowers.

To the observer, it all seems quaint in an efficient sort of way: the bidding is done on computers, with more than half of the auction participants doing their bidding off the premises. Yet here are the actual flowers, right under your nose. Within hours they could be in a bouquet on your dining room table. And flowers are such an all-purpose commodity – wedding, funerals, birthdays, Valentine’s Day – they practically sell themselves.

But there’s another surprise: the flower business and the Netherland’s leadership position in it have been ‘disrupted’ by the internet, the economic crisis, competition from new low-cost growers and changing consumer tastes. Shortly after 2009, Royal FloraHolland’s consistent growth trajectory – on the up since the cooperative was founded in 1911 – ground to a halt.

A 2015 report on the market conducted by Rabobank showed consumer spending on flowers for the previous five years had been absolutely flat while customers were from supermarkets rather than specialist florists, due in large part to constraints on disposable income in the wake of the economic crisis.

Then there’s increasing competition from low-cost flower-producing countries near the equator – Colombia, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Kenya and Malaysia – all of which have lower production costs. Better and cheaper transport – improvements in sea containers, example – meant these low – cost producers could also export globally.

It’s an effective combination and it is eroding the flower market: in 2003, Japan – one of the world’s top three flower importers along with Western Europe and the US – imported 10% of its flowers from Colombia; in 2013, that number had increased to 26%, according to the Rabobank study. By comparison, Japan’s import of flowers from the Netherlands had dropped from 8% in 2003 to just 2% in 2013. The Dutch share of the global flower market had dropped from 58% in 2003 to 52% in 2013, with exports going mainly to Germany, France and the UK – still dominant, but shrinking. And with growers able to deal directly with retail customers via the internet, the entire Royal FloraHolland cooperative auction business model was becoming less relevant.

In January 2014, Royal FloraHolland appointed a new CEO, Lucas Vos, who lost no time in reviewing the cooperative’s operations. His changes and the return of shoppers buying in florists saw solid improvements. In 2016, the consumption of flowers and house-plants in Europe rose by 1% to €35.9 billion. Emerging markets such as Brazil, Mexico, China and India are helping to drive growth – despite becoming flower producers themselves.

The Netherland’s history-conscious florists have chosen to move with the times. Opening Royal FloraHolland’s auction floor to tourists has also helped increase interest in the 125-year-old procedure. Today, visitors from around the world can witness the flower auction firsthand, and through an information-packed digital tour get to fully understand what goes on behind the scenes of this genuinely Dutch institution.

COMMENTS