MUSLIMS ENTER AMERICAN POLITICS

- 10 Nov - 16 Nov, 2018

I’ve lately been enjoying an experience that has become too rare for me, and one that felt good in the sense of feeling healthy, good for the soul. What I’ve been doing is reading an ambitious 639-page novel. And the experience of doing that – the act of doing that; Ursula Le Guin rightly points out that “reading is an act; you do it” – has helped remind me of the historical nature of the society I grew up in, and of what has become of that society today.

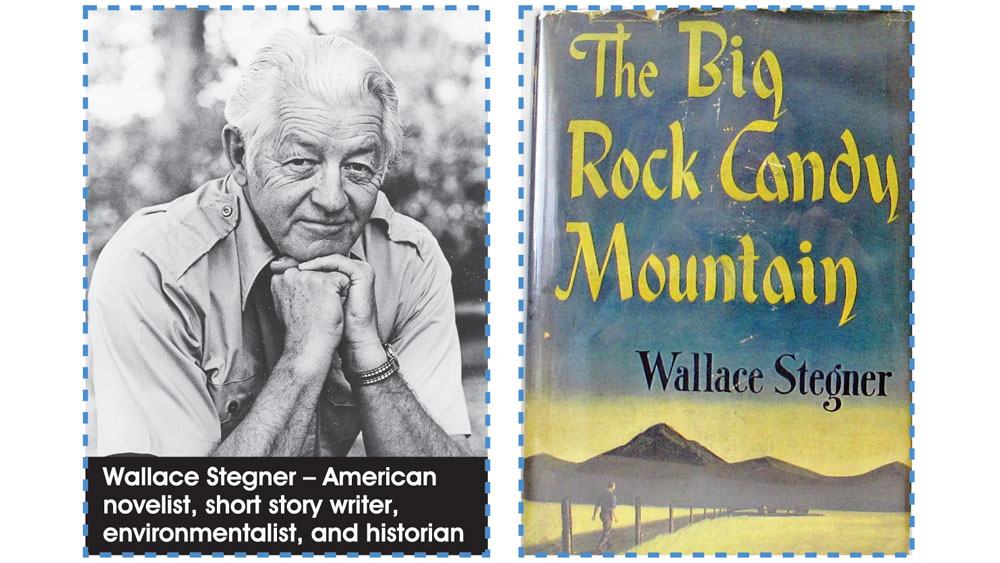

The novel I’ve been reading is The Big Rock Candy Mountain by Wallace Stegner. It’s about the migratory, hardscrabble life of an American family chasing elusive wealth and stability in a string of towns and cities around the vast western areas of the United States and Canada through the early decades of the twentieth century. The passage that especially jumped out at me was about the grown younger son driving west towards “home” from university to visit his parents, who have just moved towns yet again:

“But going home where? he said. Where do I belong in this? Going home to Reno? I’ve never been in Reno more than six hours at a time in my life. Going home to Tahoe, to a summer cottage that I haven’t ever seen that isn’t even quite completed yet? Or going home to Salt Lake, only to go right on through across the Salt Desert and the little brown dancing hills, through Battle Mountain and Wells and Winnemucca and the dusty towns of the Great Basin that are only specks on a map, that have no hold on me? Where do I belong in this country? Where is home? … Was he going home, or just to another place? It wasn’t clear.”

The Big Rock Candy Mountain is an awfully good novel. Wallace Stegner was an important writer, widely considered the first serious chronicler of the experience of living in the American West. His nonfiction history Beyond the Hundredth Meridian is essential documentation of the life and work of the great explorer and surveyor John Wesley Powell, and his later novel Angle of Repose – about the difficult marriage between a literary woman from the East and a mining engineer – is an American masterpiece. The Big Rock Candy Mountain, published in 1943 when Stegner was just 34 years old, seems to me perhaps even better than Angle of Repose, and that’s saying something.

There are a couple of reasons I’m stepping back this week from the usual hurly-burly of all that’s going on in America now, to tell you about this very fine novel published 75 years ago. One reason is that the novel itself portrays some things that ring true about what it’s like to grow up and live in American society: the chronic rootlessness; the elusive sense of and longing for “home” (which I played on in the title and themes of my own recent travel book Home Free: An American Road Trip); the grasping for a vaguely promised prosperity always somewhere further west, over the horizon. And, although the history and particulars of Pakistani experience are different, the questions of who we are and where we’re going – as individuals, as communities, as human beings – are universal. Are you Pakistani, or Muslim, or Punjabi? Did your grandparents migrate from India? Whatever your family’s particular version of the Pakistani story, it’s not fundamentally unlike the American family in Stegner’s American novel.

But another reason is simply to share with you how refreshing and nourishing it feels to read a sustained, well-crafted narrative delivered by a master of English prose. The Big Rock Candy Mountain is not at all dated, but it does read like a surviving document from a lost civilisation. How many people, anymore, spare the time and attention to read any 600-page novel? Fewer than when I was growing up, I’m sure. And that’s a loss to all of us, because there were good reasons that literature and literacy – a culture of exposing oneself, systematically and sustainably, to the awareness and command of language cultivated by the best writers (whether in Urdu, English, or another language) – used to be considered non-optional aspects of individual as well as societal maturity.

During the same week I was reading The Big Rock Candy Mountain, I stepped into one of those dumb little dust-ups that are so common on Twitter: I tweeted something mildly skeptical about a widely admired American writer. The writer is a black woman, which is relevant in today’s America because I am a white man, and the demographic markers of identity too often predetermine what we presume about each other’s words and intentions, especially in social media. To make a long story short, other Twitter users “piled on” to accuse me of racism, sexism and other avatars of bad faith. My tweet had amounted to wondering whether an American’s experience of mild indignity and discomfort on an airline flight was interesting enough for many people to read and tweet about, in a world where women and children are suffering and dying in Syria and Palestine. I felt like an unwelcome guest who had made a faux pas at a polite dinner party.

So I absented myself from the thread and, at least for now, from Twitter itself. The problem with Twitter is that it makes all long stories too short, and many stories are in fact irreducibly long. It’s not good to be long-winded, but that’s something different than giving a substantial story of human experience and meaning, and one that unfolds over time, its due. One quality that makes a 600-page novel different from a tweet is that a novel always ends somewhere other than where it began. And that is a truth we can all take home with us, wherever home might be, because sustained narrative is an essential aspect of human experience. We all end up somewhere other than where we began. •

COMMENTS