DUNKI: THE PERILOUS PATH TO EUROPE

- 30 Mar - 05 Apr, 2024

In 2017, the Pakistan Council for Research in Water Resources (PCRWR) forecasted disturbing circumstances for the country following its alarming depletion of water resources. A news story titled Pakistan To Run Dry By 2025 took the nation by storm, with electronic, print and digital media covering every possible aspect of the horrors associated with the facts of the study which claimed that Pakistan has reached its ‘water stress line’ back in 1990, and traversed it in 2005, over a decade ago, and hardly anything has been done to improve the supply and sensible use of water in all these years. The situation is expected to deteriorate further if significant measures are not taken. Even numerous international organisations such as the United Nations, International Monetary Fund and World Wildlife Fund, to name a few, have conducted extensive research in the country’s water sector, predicting alarming consequences of depleting water resources.

While the harrowing image of the dry beds of River Indus has raised concerns around the country, it is especially Karachi that is at the brink of experiencing severe riots following its on-going water crisis. The city has been under the radar for its ever-altering political climate and population growth, along with climate change and groundwater exploitation by entities with vested interests. With elections just around the corner, political groups in the city are on their toes, campaigning to woo their voters to win lucrative perks as lawmakers.

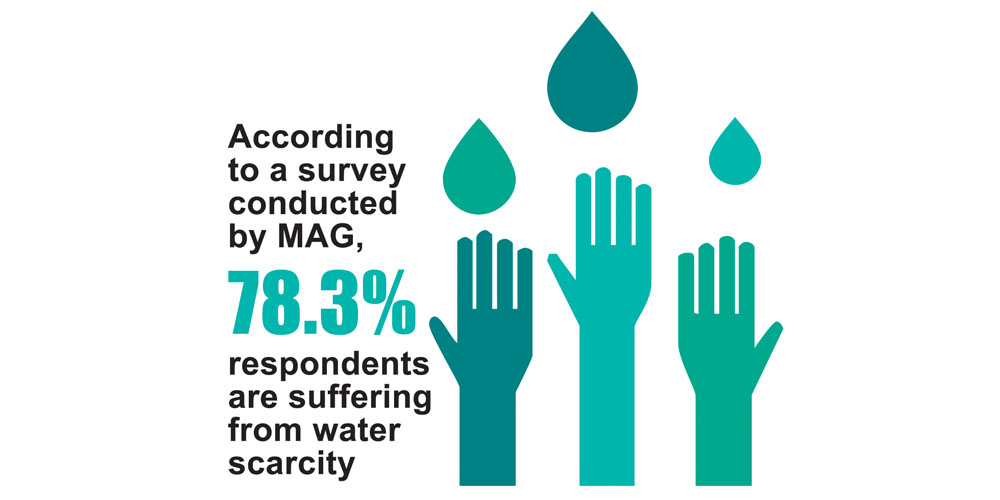

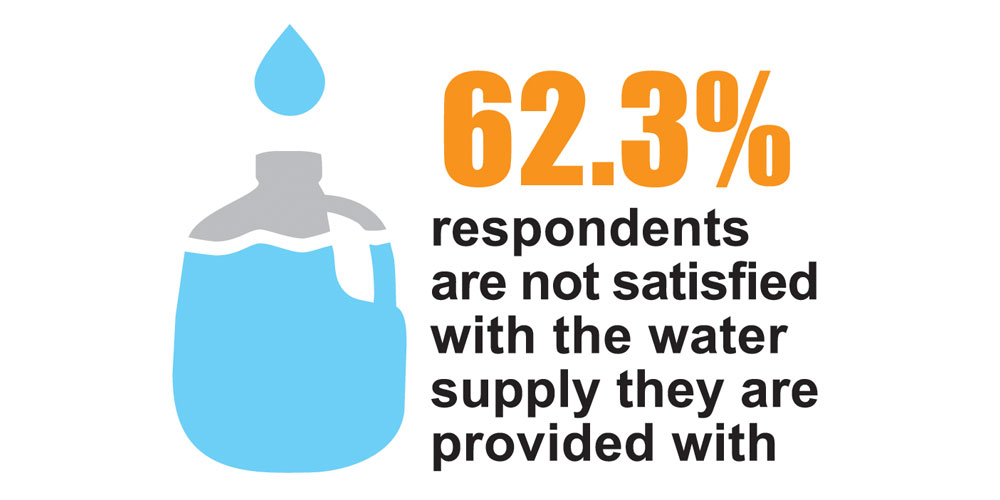

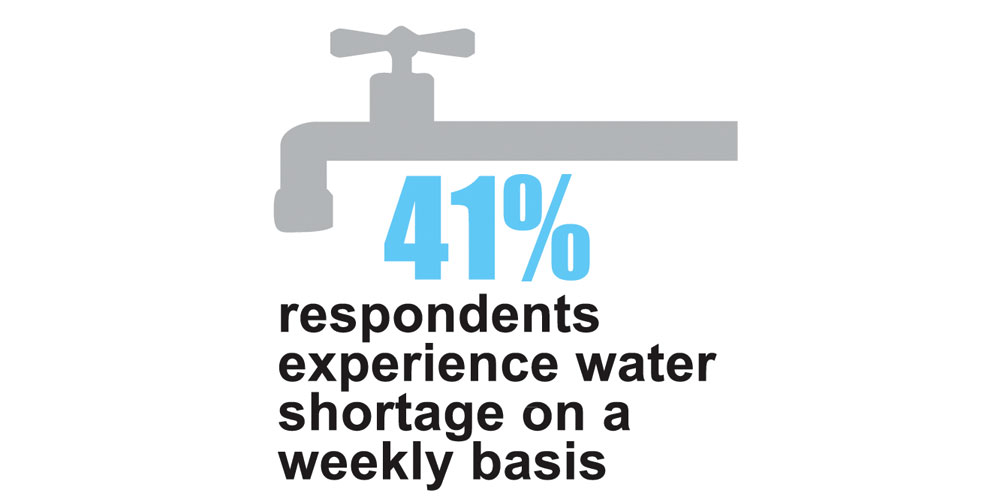

Nevertheless, the city’s issues are all intertwined and demand a collective action from all walks of life. MAG delves deep to find out the reasons behind water scarcity, woes of Karachiites experiencing water shortage, expert opinions on the issue and what officials have to say on the matter.

CITIZENS SHARE THEIR WOES

Siraj* is a 72-year-old man who resides in the Nanak Wara neighbourhood of Ranchorlane. The senior citizen shares a tormenting tale of water scarcity in his area, which according to him, is the worst considering he’s lived in the city since 1947.

“We get water supply only once a week and the water we get after waiting for so long cannot be used for cooking and drinking purposes,” he laments and pleads that the local, provincial and federal government pay heed to their miseries.

It is not just Siraj who is hit by the water scarcity. A 24-year-old resident of Agra Taj Colony, Lyari – who wishes to remain anonymous – lives with his father in their one bedroom flat. He leaves for work in the morning after the only tank in their house is filled with water, enough to last them for a few days. However, it was possible for them to do so only after installing their own water pumping machine.

“We would have never installed a water pumping machine, had we received sufficient water supply. Most people in our building pump water through it. If we do not use the machine, we would not be able to fill even one bucket. It is (already) very difficult for us to carry on with our daily chores with that little amount,” he says, adding that the area has been facing immense neglect at the hands of the authorities.

Lyari, one of the most densely populated neighbourhoods of the city, has been facing water shortage for many years now. Considering the many issues faced by the people of this locale, several political entities and criminal gangs have misused the helplessness of its residents by threatening them for their vested interests. The scribe’s sources have confirmed that certain notorious political forces have threatened to block water supply if residents do not vote for them in the upcoming elections. Such is the misery of our neglected citizens.

MAG also got in touch with Afshan*, a housewife who resides in the Garden West, and her account is no different. “We are a family of five people but the water supply we get is certainly not enough for us. It is only possible for us to continue with our daily chores through different sources,” she complains and adds, “For drinking and cooking purposes, we use mineral water, while the rest of our needs are fulfilled using the daily water supply mixed with ground water boring and wells in the building.”

This is just the tip of the iceberg. Considering the ever-growing populace of Karachi, residents have been going through tumultuous times in terms of water supply. In such a crucial scenario, all they can do is hope for the best from the next in power.

EXPERTS BELIEVE OTHERWISE

MAG reached Dr Noman Ahmed, Dean of the Faculty of Architecture and Management Sciences at the NED University, who feels the situation isn’t as dangerous as it seems in terms of the quantity of water Karachi needs.

“There are two aspects of water crisis. Firstly, we must identify whether the quantity of water available is enough for our city or not, and keeping in mind the present situation and needs, it isn’t a very dangerous situation. However, the other problem is the distribution and the governance of water supply, for it has so many flaws that the entire system is now paralysed because of it. The overall system of governance is no more able to allow smooth supply of water to the public,” Dr Noman deplores and further states, “But it is also important to mention that as our population keeps growing, we would need to increase the quantity of supply after some time because it will not be sufficient enough to cater to our daily needs.”

He also says that it is not appropriate to always blame the authorities who, he believes, have limited power in terms of policy making. “It is not right to always blame the administration of Karachi Water and Sewerage Board (KWSB), because most of the crucial decisions are taken and executed by the provincial government, and if the ministers and political mandate of the government are not interested in controlling the situation then there aren’t any prospects of change,” he points out. “This whole issue can be dealt with by bringing all the stakeholders including consumers and water experts to the table.”

HOW SERIOUS IS THE 2025 THREAT?

Environmentalists share their views

Climate change is one of the most crucial factors that had immense impact on the use of water in the city, especially after the deadly heat wave in Karachi, which drastically changed weather patterns in the South Asian region. Buying water tankers was an everyday phenomenon, for citizens were desperately looking for water around them to prevent and relieve themselves of the scorching heat’s effects. Despite our ignorance, climate change is indeed a reason for us to panic, but how serious is the 2025 threat? We ask the experts.

“By 2025, I expect very bloody civil riots in Karachi if the prevailing water crisis does not end here,” says renowned environmentalist Tofiq Pasha Mooraj, who is “very scared about the future.”

“Dams are not the answer. It will take 20 years to build a dam and how are we going to exist till then? Tarbela Dam is already empty, how are we going to fill the other dams first?

The solution to the problem lies in efforts by every individual… we need to save water on everyday basis.”

RAIN WATER HARVESTING

Shahzad Qureshi, an entrepreneur who has created an urban forest in Karachi, also shares similar thoughts. “Rain water harvesting is one way we can deal with the crisis. Secondly, it is important to plant as many trees as possible, for they act as water sheds, and thirdly, we need to recycle water to be used more than once, instead of wasting it.”

Shahzad believes that giving up will not do any good, so instead of losing hope, one must do whatever they can in their capacity to get through tough times. “We need to find out solutions to the problems we’re facing. The shortage of water is such that we need to be very careful when using it and, keep our city clean and green,” he suggests.

MANAGING DIRECTOR KWSB SENSES POLITICAL MOTIVE BEHIND THE SHORTAGE OF WATER

MAG spoke to the Managing Director of KWSB, Khalid Mehmood Shaikh, who believes that water crisis has been there for the past 10 years but the sudden uproar has a political motive. “All of the political parties competing in the upcoming elections have created much brouhaha about two things – electricity and water supply. Since electricity is not a provincial issue, they’re not making a bigger fuss about it, but through water crisis, they are questioning those in power about why they haven’t created new resources to cater to the rising demands of water. Even though I’m not denying water shortage in the city, this sudden chaos will stay for the next 25-30 days.”

He shares that it is district West that’s suffering the most in Karachi. “Our total supply is hardly 350 to 400 million gallon daily (mgd) with a mix of all line losses, but this is not the first time it’s happening. The most affected area is district West because the supply from Hub dam is hardly releasing 15mgd against the normal supply of 100mgd, which is not enough for the district,” he informs, adding, “We’re trying to accommodate this district by cutting down water supply of other districts, because of which these areas are also suffering, but less in comparison.”

The dilemma of water mafia and illegal hydrants

As a city of an extensively diverse populace, Karachi has endured the worst law and order situation. Even though it is now relatively safer for citizens, there are mafias that still operate in the city, controlling many affairs, and the supply of water is no exception. Elements operating illegal water hydrants are getting on the nerves of citizens. Despite the incessant denial by MD KWSB regarding the presence of illegal hydrants, one is yet to ignore the existence of vicious rackets functioning under the guise of influential political and religious groups, as well as dominating landlords.

Of the many notorious hydrants around the city, one exclusively caught our attention. According to our sources, a water hydrant located at Safoora Goth is legal but its operations are illegal, for it is supplying water using six tap connections instead of the two legally designated for use. It is allowed to operate for eight hours but runs for 24 hours under the nose of KWSB’s authorities. The ceaseless encroachments in the area are enough for one to suspect the presence of illegal activities. The said hydrant is apparently owned by a former police official – with political affiliations in the city – who later transferred the ownership of the hydrant to his nephew, after an enquiry into his disrepute took place. The officer is said to have taken an early retirement but is yet to be questioned about his wrong doings.

Khalid Shaikh has denied the presence of such hydrants claiming that the administration of water board has destroyed all such illegal entities.

“We have eliminated illegal hydrants from every nook and corner of the city. People cannot run a hydrant by hiding it in a small area. Operating one needs a huge structure. There’s hardly any left in the city; there maybe one or two but we have registered FIRs against them and there will soon be none.”

Information from our source also points towards Bhains Colony, where approximately 500 acres of land is wasted to illegal settlements and residents are using the water supply illegally. Consequently, KWSB is helpless to even step into the area, let alone take control over the land.

There are several other factors that have worsened the situation of water distribution in the city such as:

• Illegal construction of slums and concrete homes upon sewerage lines

• Settlement of people coming to Karachi from all over the country.

• Illegal connections in neighbourhoods across the city using main water supply lines.

Measures to secure the future

Is KWSB taking any measures to save water for the future or is it waiting for the situation to worsen in the months to come? Here’s what MD KWSB has to say. “Our project of the 100mgd pumping station will be completed in the next eight to nine months. Then, we have another of 65mgd to be completed in roughly a year and a half. There’s also the K4 project which is targeted towards 260mgd, and that will complete in roughly two years. Other than that we are also working on our recycling project. So there’s a lot that we’re doing to deal with the crisis and secure the future.” •

COMMENTS