DUNKI: THE PERILOUS PATH TO EUROPE

- 30 Mar - 05 Apr, 2024

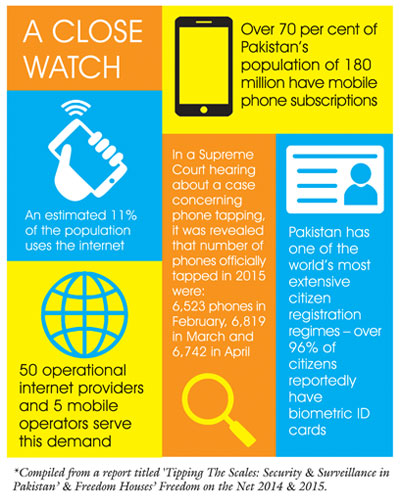

It’s 2016, not George Orwell’s 1984 and Pakistanis are tech-savvy humans who live and breathe in a democracy, unlike the people of Oceania who constantly lived under threat and scrutiny by the Party that ruled them. Sadly, it will not take long for a twist of fate, as the nation is on the brink of being inspected acutely just like the citizens of the fictional superstate. Although a piece of fiction in its entirety, Orwell’s dystopian novel, penned down nearly 67 years ago, somehow resembles the life of people living the world over, especially Pakistanis, as it pretty much sums up the current state of affairs.

Lately, local news channels and newspapers gave massive coverage to an issue, which would rather not be of enough importance to a villager, but for an urbanite, this breaking news became twice as controversial as it was already. Developed and civilised countries make laws and legislations, and make their implementation mandatory; however, in our part of the world things are slightly shadier. Laws that are meant to instil a sense of protection are becoming a cause of sleeping disorders. The Prevention of Electronic Crimes Bill (PECB), passed by the National Assembly of Pakistan on March 13, 2016 is one such bone of contention. The swift escalation of cyber crimes in the country are said to be an inevitable reason that led towards the drafting of this bill. At present it is expected to be slated in Senate where further debate will be carried on to either reject the bill or make it a law with a majority of votes.

So, what is this bill brouhaha all about? What makes it controversial or somewhat vicious? What is its purpose? Who will benefit once it is passed? What is the urgency of getting it approved through legislation? What makes it so inhumane, as deemed by a majority? Is it being blown out of proportion or the protest surrounding it is justified? The questions are aplenty and the answers sparse, hidden behind an Iron Curtain. Let’s dissect and examine the much debated cyber crime bill step-by-step and hear what the experts have to say.

“Technology is literally intertwined into everything we do. In the coming years they (digital rights) will become increasingly more important. And whether people realize it now or not, the cybercrime bill – if passed – is going to be a constant thorn in their side.” – Nighat Dad, Digital Rights Foundation

GOVERNMENT’S PERSPECTIVE

The Minister of State for Information Technology, Anusha Rehman responded to the criticism last year and presented an explanation in the National Assembly’s Standing Committee on Information Technology stating that the image surrounding the bill was not ‘as gloomy as painted by the anti-bill lobby.’

She further explained that the bill protected the interests of the foreign investors and provided local businesses with a bail out option. Rehman said the bill does not hold them accountable for the offensive content kept on the internet by an individual. It does not accuse an individual, unless their intent is proven and then the bill allows the mentioned law enforcement agencies to seize the data and equipment as proof.

THE NEED TO LEGISLATE CYBER LAWS IN PAKISTAN

The need is inevitable as suggested by Shahzad Ahmed, an internet rights activist and Country Director of Bytes for All Pakistan, a research think tank and human rights organisation that deals with Information and Communication Technologies. Commenting on the subject he says, “Pakistan needs a cyber crime law which should be pro-people with a human rights approach; clear and explicit in its mandates to deal with online crimes. However, a law with a ‘security’ approach intended to curb fundamental freedom is what we are struggling against. This freedom includes access to information, freedom of expression, right to privacy, online assembly for peaceful purposes and online associations.”

Apparently, there is a dire need of laws to tackle electronic crimes that include credit card frauds and scams that cost people a considerable amount of loss financially. A law drafted with a much favourable approach towards the citizens will help curb crime and protect the digital rights of people, simultaneously.

The Executive Director of the Digital Rights Foundation, Nighat Dad, who is also a lawyer and a vocal digital rights activist states that most people are not aware of what cybercrimes entail, let alone know how to act against them. The bill could have helped remedy that lack of knowledge and action. And it is not a question of what part of the society would benefit the most – hardly any people exist that won’t benefit from the bill. We all use phones, so many of us have laptops. Using the internet on one’s phone is such a common thing.

Around the World

A high profile legal dispute between Apple and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) took a serious turn, when the agency’s officials asked the smartphone giant to allow them access into one of its users’ cellphone following a terrorism investigation. Though Apple denied its request, but the FBI committed a security breach and accessed the device. However, it has now raised a debate between law enforcement authorities and technological firms over the rights of data access and privacy.

The example of contentious Wiki Leaks released by Edward Snowden, a former National Security Agency contractor, raised concerns over the issue of data privacy and excessive surveillance by authorities – a sensitive issue indeed.

Our eastern neighbours are also not an exception, as internet censorship is selectively practised by the federal as well as the provincial administrations in India. Though the authorities have not come up with a policy to block internet access on a substantial scale, but methods to erase content have become quite prevalent recently.

A BRIEF SUMMARY

The legislation is comprised of seven chapters and is expected to be applied on “every citizen of Pakistan wherever he may be, and also to every other person for the time being in Pakistan.”

The chief purpose of the bill lies in introducing a policy structure and various procedures to deal with heightened cybercrimes throughout the country.

The first chapter consists of various definitions used in the legislation as well as their legal limitations. For instance, the bill defines the term “access to data” as possessing authority to read, copy, use, alter, or erase any kind of data held in or produced through any device or a system of information.

The second chapter focuses on the offences and punishments following them. The felonies include illegal access to different information systems and data, illicit plagiarism or transfer of data, glorifying hate speech, electronic forgery, cyber terrorism, online stalking, electronic fraud, unlawful issuance of SIM cards etc, so as to punish a law-breaching person. The bill states to implement, “Unless context provides otherwise, any other expression used in this Act or rules framed thereunder but not defined in the Act, shall have meanings assigned to the expression in the Pakistan Penal Code, 1860 (XLV of 1860), the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898 (V of 1898) and the Qanoon-e-Shahadat Order, 1984 (X of 1984), as the case may be.”

Chapter three encompasses details regarding the establishment of investigation and tribunal teams and the procedural controls. This part of the PECB discusses confiscation of data for scrutiny, warrants to unveil the data, authority to check, copy demand or even an individual for the purpose of interrogating the case. If need be, service providers could as well be questioned in case of suspicion related to criminal activity.

The fourth chapter talks about international cooperation which the Federal Administration will be responsible for seeking and permitting mutual assistance. The authorities may decline to comply with an appeal made by a foreign administration, an agency or various international organisations if the appeals cause concern to an offense that may compromise one’s own national interest.

The fifth chapter identifies the felony trails, its prosecution, disclosure of fine amount, compensation payment and if needed, an opinion for an expert partial advisor to court. An appeal should be made at least 30 days from the date of trial.

The sixth chapter elucidates essential preventative methods against cyber felonies. Those in authority would be held liable for issuing guidelines for preventing offences under this particular act. A rapid response team will also be created to curb possible threats and assaults. The bill tends to cater several uncategorised issues under its seventh chapter. It mentions that the Federal government has the authority to create rules that include an officer’s training, authorities and powers of an investigation agency, joint investigation teams, Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), teams working under real time intelligence etc.

The regular crimes that involve broad classifications of online activities such as theft (of money, data, documents, software piracy, intellectual property, trademark violations, copyright infringement etc.), deception, sale of unauthorised or forged items through the internet, money laundering, gambling, email hoax (emails which appear to be created by a single source but are in fact sent by another), propaganda, printing and allocating defamatory material, victimising an individual online, illegal access to various computer networks, hacking, bombarding emails, data alteration, use of malware, worms, viruses, Trojan attacks, and web jacking.

LOOPHOLES AND VAGUE TERMS

A key issue with the bill is its recognition and the trials to be followed, as it is quite borderless and faceless. Understanding the bill is rather difficult for a layman as it is filled with vague expressions and terms that have been used to describe various crimes. One of the many is Section 3 in the bill which states, “Whoever intentionally gains unauthorized access to any information system or data shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three months or with a fine up to Rs. 50,000 or both,” while there is another one from Section 4 that states, “Whoever intentionally and without authorization copies or otherwise transmits or causes to be transmitted any data shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to six months, or with fine up to Rs. 100,000 or with both.”

Now words like these could be applied on anyone practically. For instance, if you are copying your friend’s work and transferring it online, well, that can make you a criminal offender, considering the words in their literal form. Apparently, you may not go through a trial for stealing his homework, but the fact is that the words are vulnerable to be misinterpreted and misused by the devious. A lot of terms have been left undefined which leaves an individual at the risk of being charged with offences mentioned in the bill. There is no protection mechanism available if the authority is used against an innocent citizen. Anything said or written in order to express one’s political opinions, such as those coming from media, civil society and the public as well, particularly those criticising the government or its authorities can label one with a criminal tag. Things that have been left ambiguous are open to be manipulated, which will eventually hurt the public more than anyone else.

“If the draconian provisions persist, it would work for the people in power as it would make it easier to curb down on dissent.” – Sana Saleem, Bolo Bhi

DIGGING THE LOOPHOLES IN PREVENTION OF ELECTRONIC CRIMES BILL 2016

The Bill restricts you from

• Sending emails

• Posting pictures without permission

• Tweet or retweet a funny meme or anything which may otherwise be considered notorious

• Make a comment on the internet regarding the government or countries having friendly relations with Pakistan

• Sending an SMS without the receiver’s permission

• Having an opinion on any political matter

FINDING A BETTER OUTLET

In order to make the Bill more people- friendly and less threatening, Shahzad Ahmed suggests that the government must, “remove the clauses which can harm online liberties/fundamental rights. We call upon the parliament and the government to introduce protection mechanisms for the citizens first before promulgating this legislation. We urge the government to constitute a capable, independent Privacy Commissioner and strengthen National Commission on Human Rights (NCHR) as a safeguard against any human rights violations. We also urge the Upper House in the parliament to return the bill to the Lower House with recommendations to amend it taking a multi-stakeholder and human rights based approach on this sensitive legislation.”

Sana Saleem, the Director of Bolo Bhi, a civil society organization working on internet freedom, privacy and gender in Pakistan, has similar views, “A good piece of legislation needs to have a tighter language; most importantly the process of law making needs to be democratic, open, transparent and accountable. We’ve seen some brilliant legislations pass in the past few years on women’s rights and the same can be done when it comes to other legislations. It should be done in consultation with the civil society, experts in cyber law policy and technology.”

No one wants to witness a Pakistan where approximately 30 million of its internet users could be held punishable with imprisonment, if the wished-for Prevention of Electronic Crimes Bill 2016 is approved by majority of the Senate. It would have been easier to assimilate if only the clauses targeted terrorism and cyber criminals, as per the government’s claim. The law as viewed by experts show a completely opposite picture and instead makes Pakistan a sanctuary for extremists. If political gains and face-saving are not just an objective, Pakistanis can hope the future favours their digital and human rights; after all one can always dream of living in Utopia where no Big Brother watches you!

COMMENTS