THREADS OF SUCCESS

- 06 Apr - 12 Apr, 2024

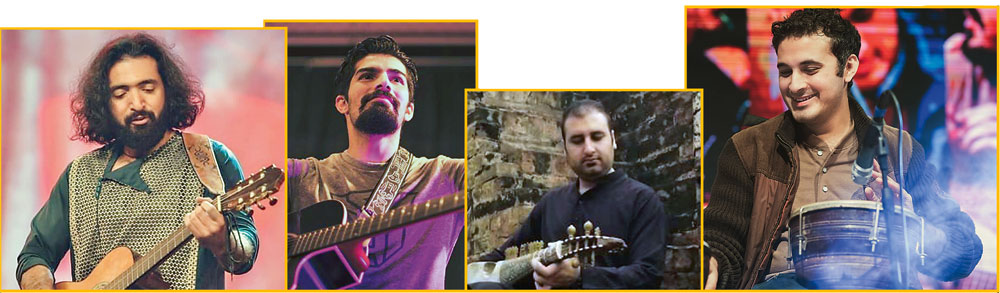

There is a common misconception that the Pashtun youth is lagging behind in terms of talent, exposure, and opportunities. Yes, a little bit here and there but at no point has it become a roadblock. A little shy of a decade, four young men – Aamer Shafiq, Farhan Bogra, Shiraz Khan, Sparlay Rawail – came together to form a folk-rock band, Khumariyaam and with their combined passion for music and their love and pride for their heritage, has resulted in music that touches hearts. In a conversation with Sparlay, we talk about resurrecting dying instruments, engaging hearts with soulful music and making the dreams come true along the way.

A better question would be why we stuck with the instrument that we chose initially. We felt the need to represent our provincial instruments at national level. 10 years ago, it was the rubab, five years ago it was the khatak dhol and three years ago it was the Pashtun sitar. These are the instruments that we added and we feel the need to reintegrate them in a new manner in Pashtun music.

It is similar more or less. Since our music doesn’t have any lyrics, everyone can relate to it. Be it at home or abroad, everybody seems to love it. When we do a little singing here and there, people don’t understand but they like it.

The common misconception about the Pashtun youth is that it is not open-minded. That’s not the case. It’s not like our music is a radical change to Pashtun music. It’s quite Pashto, just a little contemporary, like the youth itself. No specific incident but here is a fact; the sale of rubabs has gone up exponentially and so has the number of rubab makers. Sometimes, tracks run their course and don’t get many views on social media, but with our tracks, we have 10 to 20 thousand views across multiple platforms. It means that people are listening to our music over and over again and have developed a certain liking for it.

I disagree with that. After this new ethnic movement of music in Pakistan there are a lot of bands that are looking towards making contemporary cultural music. But if you are referring to folk music, the way it is and has been played for the past couple of centuries, then yes, I would agree. But there are bands that have highlighted that kind of music in its simple and plain form like it has been played for the past hundred years. Live is a different story but creating that live feel in the studio is very important and sometimes, the recordings don’t come across very nicely. We don’t take it as a responsibility. Our main focus is obviously to preserve and evolve our cultural music but it is also to have fun on stage and for the audience to have a good time. We primarily just focus on being ourselves and don’t think of it as a big responsibility. It just naturally fell onto us and we are more than happy to fulfil it and try to take this music to anywhere in the world.

Locals absolutely loved it. When the band first started, the music was localised to universities mainly. Over the years, their taste has evolved and so has our style but they evolved in a very nice harmony.

I think bringing forward just one thing, Attan or otherwise, isn’t our aim. The idea is to bring forward the notion that KPK cares about its culture and its folk music. The idea is to change the notion that folk music and folk instruments are only played by people of a certain class. It doesn’t mean they have to be looked down for it. That’s the idea that we in KPK care about our culture, our practices, and our music.

Shiraz’s father himself is a drummer and maybe there is a subconscious connection there. Ever since he was little and didn’t even have instruments, he would play with pots and pans. He had an idea that he’d like percussions. It was when he joined the university’s music society that he came across this instrument which was losing its popularity. It wasn’t a conscious decision but at the same time, it was. Subconsciously they wanted a percussions’ instruments when Farhan and Shiraz first started playing and they made a conscious choice to use an instrument which was dying and needed to be brought back.

To have a lifetime of friendship, music, brotherhood, and fun on stage. Also, touring the world as a world music ensemble, signing with some sort of indie band record label. The priority will always be the ultimate dream.

It was an accidental trio. The three members came together thanks to a trickledown effect at the university. They were playing in the music society and their main goal was to have fun. Somewhere down the line, the combination clicked and they made a conscious effort to not just stick to Pashto music but to do something new. And then when I joined the band, for a year or two, we just played music. There was some conscious effort but when we started playing prolifically, we realised the importance of what we were doing because people reacted so strongly to it.

We need to educate the people that they are about four to five degrees you can do in recorded studio technology. In layman terms, when you are playing live the amplification, the sound hits you in the chest, and it’s a very physical experience. When the same thing is recorded, the recording of four instruments, it simply can’t capture what you’re trying to play. Which is why live performances are a completely different experience and on record, everything just mellows down. It doesn’t feel full. We call ourselves a live band because we are very interactive with the audience and you can’t replicate that in a recording. In studios, we have to amp everything up to make it sound fuller and thumpy. When we play live, we ask our audience to put down their phones and just enjoy because the video will never translate a live act. It isn’t the instruments that we play, it’s just how the music design has evolved over the years.

Surreal! It was something else.

We’ve done quite a few singles now and it’s about time we release an album. With international tours and Coke on our plate, it has become delayed but now we’re on it.

COMMENTS