An Epidemic

- 13 Apr - 19 Apr, 2024

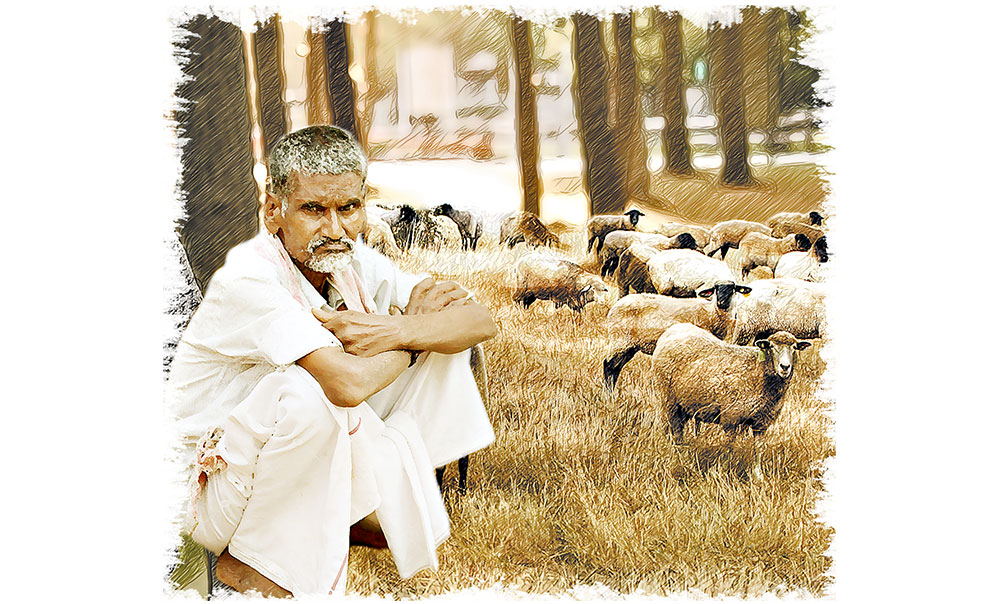

He used to roast corn on the cob beautifully, parching it carefully over a low fire so that every grain would gleam like gold and taste like honey and smell as fragrant and sweet as the fragrance of earth repeatedly on every side as though he had known that particular cob for years. He would talk to it like a friend, treat it as gently and kindly and affectionately as though it were some kinsman, as though it were his own brother. Of course other people used to roast cobs, but who could compare with him? Their cobs used to be so half-baked, so tasteless, so altogether ordinary, that they scarcely deserved the name. And yet the self-same cob in Kalu Bhangi’s hands became completely transformed, and would come off the fire like a new bride gleaming in gold in her wedding dress. I think that the cob itself would get an inkling of the great love which Kalu Bhangi bore it, otherwise where could a lifeless thing acquire such charm? I used to thoroughly enjoy the cobs which he prepared, and would eat them secretly with great delight. Once I was caught and got a real good thrashing. So did Kalu Bhangi,

poor fellow, but the next day there he was at our bungalow as usual.

Well, that’s all; there’s nothing else of interest to be said about him that I can recollect. I grew up from boyhood to youth and Kalu Bhangi stayed just the same. Now he was of less interest to me; in fact you may say of no interest at all. True, his character occasionally attracted my attention. Those were the days when I had just begun to write, and to help my study of character I would sometimes question him, keeping a fountain-pen and pad by me to take notes.

‘Kalu Bhangi, is there anything special about your life?’

‘How do you mean, Chhote Sahib?’

‘Anything special, out of the ordinary, unusual?’

‘No Chhote Sahib.’

‘All right, tell me then, what do you do with your pay?’

‘What do I do with my pay?’ He would think. I get eight rupees. I spend four rupees on atta, one rupee on salt, one rupee on tobacco, eight annas on molasses, four annas on spices. How much is that, Chhote Sahib?’

‘Seven rupees. And every month I pay the money-lender one rupee. I borrow the money from him to get my clothes made, don’t I? I need two sets a year; a blanket I’ve already got, but still, I need two lots of clothes, don’t I? And Chhote Sahib, if the Bade Sahib would raise my pay to nine rupees, I’d really be in clover.’

‘How so?’

‘I’d get a rupee’s worth of ghee and make maize parathas. I’ve never had maize parathas, master. I’d love to try them.’

Now, I ask you, how can I write a story about his eight rupees? Then when I got married, when the nights seemed starry and full of joy, and the fragrance of honey and musk and the wild rose came in from the nearby jungle, and you could see the deer leaping and the stars seemed to bend down and whisper in your ear – then too I would take a pencil and paper and go and look for him.

‘Kalu Bhangi, haven’t you got married?’

‘No, Chhote Sahib.’

‘Why?’

‘I’m the only sweeper in this district, Chhote Sahib, There’s no other for miles around. So how could I get married?’

Another blind alley. I tried again. ‘And don’t you wish you could have done?’ I hoped this might lead to something.

‘Done what, Sahib?’

‘Don’t you want to be in love with somebody? Perhaps you’ve been in love with someone and that’s why you don’t marry?’

‘What do you mean – been in love with someone, Chhote Sahib?’

‘Well, people fall in love with women.’

‘Fall in love, Chhote Sahib? They get married, and maybe big people fall in love too, but I’ve never heard of anyone like me falling in love. And as for not getting married, well I’ve told you why I never got married. How could I get married?’

How could I answer that?

‘Don’t you feel sorry, Kalu Bhangi?’

‘What about, Chhote Sahib?’

After that I gave up, and abandoned the idea of writing about him. Eight years ago Kalu Bhangi died. He, who had never been ill, suddenly fell ill so seriously that he never rose from his sick bed again. He was admitted to the hospital and put in a ward of his own. The compounder would stand as far away as he could when he administered his medicine. An orderly would put his food inside the room and come away. He would clean his own dishes, make his own bed. And when he died the police saw to the disposal of his body, because he left no heir. He had been with us for twenty years, but of course he was not related to us. And so his last pay-packet too went to the government because there was no one to inherit it. Even on the day he died nothing out of the ordinary happened, the hospital opened, the doctor wrote his prescriptions, the compounder made them, the patients received their medicine and returned home – a day just like any other day.

And just like any other day the hospital closed and we all went home, took our meals in peace, listened to the radio, got into bed and went to sleep. When we got up next morning we heard the police had kindly disposed of Kalu Bhangi’s body. Whereupon the Doctor Sahib’s cow and the Compounder Sahib’s goat would neither eat nor drink for two days, but stood outside the ward lowing and bleating uselessly. Well, animals are like that, aren’t they?

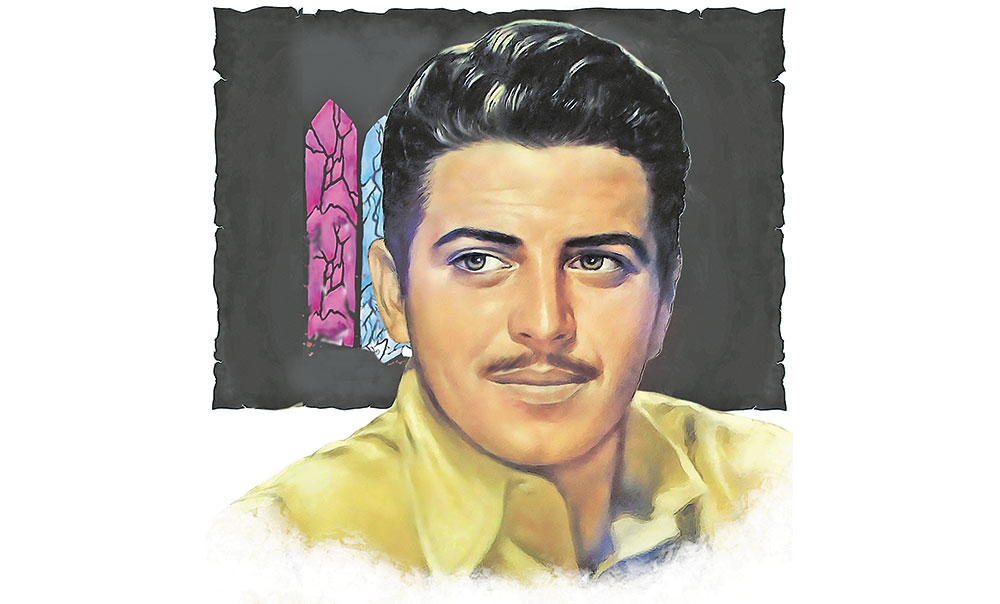

What! You here again with your broom? Well? What do you want? Come now! I’ve written down everything about you, haven’t I? What are you still standing there for? Why do you still pester me? For God’s sake go away! Have I forgotten anything? Have I missed anything out? Your name: Kalu Bhangi; Occupation: sweeper. Never left this district. Never married. Never been in love. No momentous events in your life. Nothing to thrill you – as your beloved’s lips, or the kisses of your child, or the poems of Ghalib* thrill you. An absolutely uneventful life. What can I write? What else can I write? Pay: eight rupees. Four rupees atta, four annas spices, one rupee salt, one rupee tobacco, eight annas tea, four annas molasses. That’s seven rupees. And one rupee for the moneylender, eight. But eight rupees don’t make a story. These days even people earning twenty, fifty, even a hundred rupees aren’t interesting enough to write stories about, so it’s quite certain that you cannot write about someone who only earns eight. So what can I write about you? Now take Khilji. He was born in a lower middle-class family and his parents have him a fair education up to middle. Then he passed the qualifying examination to be a compounder. He is young and full of life, with all that implies. He can wear a clean white shalwar, have his shirt starched, use brilliantine on his hair and keep it well combed. The government provides him with quarter, like a little bungalow. If the doctor makes a slip he can pocket the fees, and he can make love to the good-looking patients. Remember that business about Nuran? Nuran came from Bhita. A silly young creature of about sixteen to seventeen. She’d be sure to catch your eyes even if she were four miles away, like a cinema poster. She was a complete fool. She had accepted the attention of two young men of her village. When the headman’s son was with her she was his. And when the patwari’s boy turned up she would feel attracted to him. And she couldn’t decide between them. Generally people think of love as being a very clear-cut, certain, definite thing: but the fact is that it is usually a very unstable, vacillating, uncertain sort of condition. You feel that you love one person and also another person, or perhaps no one at all. And even if you are in love, it’s such a temporary, fickle, passing feeling, that no sooner is the object of your affection out of sight than it evaporates. Your feeling is quite sincere, but it doesn’t last. And that’s why Nuran couldn’t make up her mind. Her heart throbbed for the headman’s son, and yet no sooner had she looked into the eyes of the patwari’s boy then her heart would begin to beat fast and she would feel as though she were alone in a little boat in the midst of a vast ocean, and rolling waves on all sides, holding a fragile oar in her hand; and the boat would begin to rock, and gently go on rocking, and she would grab the fragile oar with her fragile hands just as it was slipping from her grasp, and gently catch her breath, slowly lower her eyes, and let her hair fall in disorder; and the sea would seem to whirl around her, and ever-widening circles would spread over its surface and a deathly stillness would descend on all sides and her heart would suddenly stop beating in alarm, and then someone would hold her tight in his arms. Ah! When she gazed at the patwari’s boy that was just how she felt. And she just couldn’t decide between the two. Headman’s son, partwari’s son… patwari’s son, headman’s son… She had pledged herself to both of them, promised to marry both of them, was dying of love for both of them. The result was that they fought each other till blood streamed down, and when enough young blood had been let, they got angry with themselves for being such fools. And first of all the headman’s son arrived on the scene with a knife and tried to kill Nuran, and she was wounded in the arm. And then the patwari’s boy came, determined to take her life, and she was wounded in the foot. But she survived because she was taken to hospital in time and got proper treatment.

Well, even hospital people are human. Beauty affects the heart – like an injection. The effect may be slight or it may be considerable, but there will certainly be some effect. In this case the effect on the doctor was slight, on the compounder it was considerable. Khilji gave himself up heart and soul to look after Nuran. Exactly the same thing had happened before. Before Nuran it had been Beguman, and before her, Reshman, and before her, Janaki. But these were Khilji’s unsuccessful love affairs, because these were all married women. In fact Reshman was the mother of a child too. Yes, there were not only children, but parents, and husbands and the husbands’ hostile glares which seemed to Khilji to pierce right into his heart, seeking to find out and explore every corner of his hidden desires. What could poor Khilji do? Circumstances had defeated him. He loved them all in turn – Beguman’s and Reshman, and Janaki too. He used to give sweets to Beguman’s brother every day; he used to carry Reshman’s little boy about with him all day long. Janaki was very fond of flowers; Khilji would get up and go out very early every morning, before light, and pick bunches of beautiful red poppies to bring her. He gave them his attention. But when the time came and Beguman was cured she went away with her husband, weeping, and when Reshman was cured she took her son and departed. And when Janaki was cured and it was time to go, she took the flowers which Khilji had given her and pressed them to her heart, and her eyes were brimming with tears as she gave her husband her hand and went off with him, until they at last disappeared beneath the crest of the hill.

COMMENTS